The Housing Cost Impact of Urban Containment in Portland, Oregon

February 1, 2018

Authors: Gerard C.S. Mildner, Portland State University

Publishers: Whitepaper

Portland, Oregon’s urban growth boundary (UGB) has been an iconic policy for the urban planning profession in the past 40 years. The boundary is an element of an urban containment system to promote farm and forest protection and encourage the development of dense, walkable urban spaces. In these physical terms, the policy has been quite successful. Rural areas of the Willamette Valley remain productive farmland, specializing in wine, fruits, hazelnuts, nursery plants, and other agricultural products. And Portland’s downtown is recognized as a well-designed urban core, with numerous greenspaces and parks and revitalized downtown and urban neighborhoods. At the same time, housing prices and rents in the Portland metropolitan area have risen at rates significantly above the rate of inflation, with the City of Portland declaring a housing emergency. Oregon’s landmark land use regulations have been side-tracked in recent years by a layering of local regulations that have reduced housing production and created a regional housing crisis.

Portland, Oregon’s urban growth boundary (UGB) has been an iconic policy for the urban planning profession in the past 40 years. The boundary is an element of an urban containment system to promote farm and forest protection and encourage the development of dense, walkable urban spaces. In these physical terms, the policy has been quite successful. Rural areas of the Willamette Valley remain productive farmland, specializing in wine, fruits, hazelnuts, nursery plants, and other agricultural products. And Portland’s downtown is recognized as a well-designed urban core, with numerous greenspaces and parks and revitalized downtown and urban neighborhoods. At the same time, housing prices and rents in the Portland metropolitan area have risen at rates significantly above the rate of inflation, with the City of Portland declaring a housing emergency. Oregon’s landmark land use regulations have been side-tracked in recent years by a layering of local regulations that have reduced housing production and created a regional housing crisis.

Development of Portland’s UGB

Under the State of Oregon’s land use planning system, all cities within the state are mandated to have urban growth boundaries to contain its residential and commercial activities. Cities are required to analyze the capacity of their urban growth boundaries on a regular basis to ensure that 20 years’ worth of population and employment growth can be maintained within these boundaries.

Starting in the early 1990s, development within the Portland region accelerated and housing costs and land costs began to increase. Circa 1995, the Portland metropolitan region achieved average housing prices that, for the first time in history, exceeded the national average for urban areas. Spurred by policies promoting economic development, Washington County attracted major investments by Intel and other information technology firms.

Simultaneously, the region engaged in a process to produce a long-term development plan, known as the 2040 Growth Plan. In the language of the debate, citizens were told that the region faced a choice of “growing up or growing out.” The region could continue with previous policies to provide generous amounts of land for low-density fringe development (i.e., “growing out”), or it could minimize the need to expand into exurban farmland by promoting higher density inside the UGB (i.e., “growing up”).

Ignoring for a moment the pejorative language represented by the “growing out versus growing up” choice (who doesn’t want to be a grown-up?), a conscious decision was made to seek future growth within the existing urban growth boundary, rather than two available options: (1) promoting the development of satellite cities, or (2) promoting continued low-density development along the fringe of the urban growth boundary. The Portland-area regional government, Metro, implemented a long-standing policy known as the “Metropolitan Housing Rule” which encouraged all jurisdictions within Metro’s boundary to set aside land for a variety of housing types. As a result, much of the development in the 1990s included a mix of single family housing and multi-family units. Therefore, most jurisdictions have residential zoning that can accommodate mid- and high-rise construction, provided the demand for those products exist.

Throughout the 1990s, Metro made small UGB expansions, satisfying the desires of individual property owners, developers, and jurisdictions. State rules mandated that any urban growth boundary expansion must focus on the protection of high quality farmland to preserve the agricultural economy.

Since 1980, the area inside Portland’s UGB has expanded by 10%, while the population of the metropolitan area has grown by 78%.

Impact of the Great Recession

Like most metropolitan areas, Portland experienced significant economic dislocations resulting from the Great Recession of 2008. Portland was one of the last metropolitan areas to experience a decline in home prices, but the decline was quite severe. The average existing home price in the region declined from $311,700 in July, 2007 to $223,000 in January, 2011. The decline in home prices led to a precipitous slump in housing production, particularly in the suburban counties of the metropolitan area. Housing production in the four-county region (including Clark County, Washington) averaged 14,000 units per year in 1990-2007. By 2009, housing production fell below 4,000 units. While the total number of housing units produced has risen in recent years, the average for the last four years is 12,000 housing units per year. When comparing population growth to housing production, there is an absence of about 50,000 housing units due to the recession.

Between 1990 and 2007, 67% of housing production in the four-county region came in the form of single-family homes. This fell to 62% in 2008-12, when housing production was depressed, and further dipped to 47% single family units in 2012-16, when overall housing production had recovered.

The rising demand for apartments has led to significant rent increases which have made Portland one of the fastest appreciating rental markets in America. Those market conditions have led to considerable turmoil in city and state housing policy.

One of the ironies of the shift from a housing market dominated by single family construction in the suburbs to multi-family construction in the central city is the widespread appearance of a housing construction boom. In fact, the region has experienced a 15% decline in housing production. The dearth of single-family construction on the urban fringe has gone largely unnoticed in the local press. Few residents are aware of the 15% overall decline in housing production.

Metro’s 2015 UGB Decision

Within this context, Metro made a 2015 evaluation of the capacity of its urban growth boundary and its possible need to be expanded. Under its evolving procedures, Metro produces a population forecast, estimates the demand for employment land and residential land, measures the availability of land inside the UGB, and determines if the UGB should expand to meet the deficiency.

With that forecast in hand, Metro computes a Housing Needs Analysis to determine the number of housing units needed over the next 20 years. A similar process determines the amount of employment land needed.

Metro’s 2014 Urban Growth Report determined that the region had 10,400 surplus acres for multifamily construction, 10,300 surplus acres for single family construction, and 990 surplus acres for industrial land to meet 20 years of population growth. As a result, no additional acreage was required within the UGB for housing development or employment growth.

The problem with the 2015 MetroScope model is that land for development capacity, as represented by permitted zoning, was assumed to be buildable. Development at higher density levels requires high rent levels, which often exceed market rents in the location of the apartment buildings. Since zoning entitlements in much of the relatively low-income, low-rent neighborhoods of east Portland are quite generous, there was development capacity to handle the expected additional population growth expected over the next 20 years. In that sense, Portland’s generous zoning entitlements acted as a sponge to soak up whatever population and housing demand that Metro’s demographic forecasters threw at them.

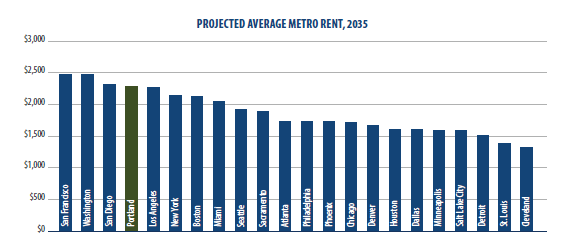

To their credit, Metro’s planners estimated the housing prices and apartment rents needed to reach those development targets. They anticipated that average rents in the Portland region would need to rise by 37% in inflation-adjusted terms in 20 years to justify the higher costs of development. Factoring in a 2.5 percent annual inflation factor, this would mean that rents would rise by 124%—more than doubling their current levels. Home prices would rise even faster in Metro’s estimation—148% in 20 years.

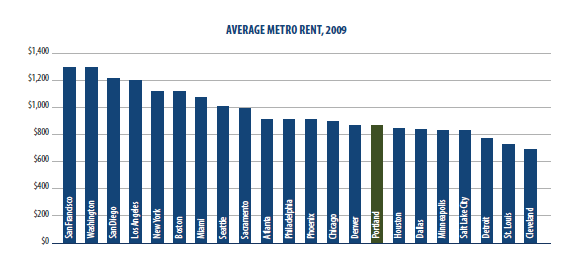

To assess what that level of appreciation would mean, I’ve arrayed the median gross rent in the Portland metropolitan area in 2009 against 21 other US metropolitan areas, selected for their size and location.

The zero-expansion result in 2015, and the incongruous housing emergency established by the City of Portland, left many planners, economists, and public officials at Metro highly unsatisfied. Staff and consultants refined the MetroScope model for the next round of UGB decisions, using a simplified pro-forma modeling sub-routine. In the revised model, several distinct development archetypes have been modeled in terms of the returns earned by the developer.

In the diagram above, we find that rents in the Portland region fall somewhere in the lower half of the distribution, competing with large metropolitan areas such as Chicago and Dallas, and west coast competitors like Phoenix, Denver, and Salt Lake City. More significantly, Portland area rents are substantially below those in the major cities in California, such as San Francisco and Los Angeles, which are important sources of employment growth for this region. Economic development agencies in the region routinely recruit Bay Area software firms, citing that while Portland may not have the same cultural or climate amenities of California, our housing is one-third less expensive and we’re a short airplane flight away. Put differently, a software firm in the Bay Area can convince some of their engineers to move to Portland, knowing that the engineer can afford to buy a nice house.

With the rent and price increases anticipated by Metro’s 20-year plan, that value proposition evaporates. If rents in Portland rise by 37% above the rate of inflation for apartments elsewhere, the large discount relative to the California cities vanishes. The engineer in Silicon Valley won’t readily accept a move to Portland, and our competitors in Denver, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, and Austin will win those firm relocation opportunities.

In practice, the strategy of absolute containment of the region’s population is likely to result in reduced job opportunities and slower economic growth. Workers will require compensation for accepting jobs in a high cost, modest amenity region. If firms cannot achieve significant cost savings from locating in Portland, expansion will occur in other cities—our mountain state competitors, cities in Texas or cities in the Southeast such as Atlanta and Charlotte. Children who grow up in the Portland area will more likely move to those cities to find employment, creating what I call the “Santa Barbara Effect.”

Our city will remain a nice place with amenities, but it won’t be a dynamic place where new employment and technology are developed. Homeowners might feel richer, but the resulting increase in home equity won’t matter until they retire and move to Arizona or Nevada. The brunt of the transition to Metro’s policy to appreciate real property assets will be felt most harshly by the poor, who don’t own property. Low-income households have been shown to be losers in regions that constrained spatial expansion in the face of population growth pressure.

Gerard Mildner is Associate Professor, School of Business at Portland State University. He can be reached via e-mail at mildnerg@pdx.edu. You can download the complete version of this article here.